Cataract Surgery Returns Much More Than Sight for Ruth Marcus

My siblings and I weren’t sure whether or not to have my mother’s cataracts removed. Ruth Marcus, matriarch/queen of our large family, is 95, lives in a nursing home, and is so out of touch with reality that we couldn’t reasonably discuss the surgery with her. She kept saying “there’s nothing wrong with my eyes!” though the only vision test she could pass was “how many fingers?” with the fingers inches from her face. She fumbled the food on her plate because she couldn’t see it. Spent her birthday surrounded by loved ones, but couldn’t tell one from another except for the noisy ones. Vestiges of the life she had loved, the six lives she had ushered into the world and tried her damnedest to perfect—all stared out from picture frames on her dresser, unnoticed.

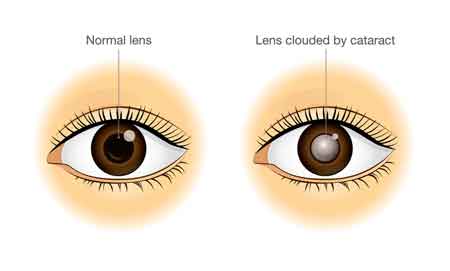

Cataracts Can Sneak Up on You

The cataracts had snuck up on us. A year earlier, Ruthie was still reading for hours a day. Out loud. The Nation. Atlantic Monthly. National Geographic. Time. Her favorite was the local paper. She would start on page 1 and recite with feeling until she got to one of two sticking points: directions to the jump page, so confusing that by the time she got there, she’d forgotten what she was reading; or reference to a name cited earlier in the article, to which she would spout, “Who the hell is that?” Then she’d take it from the top. Our home health aides would recite the front page of the newspaper from memory when we stopped by.

If you visit an aging loved one frequently, you can’t see the day-to-day changes; so none of us can say when our mom stopped reading. Stopped seeing our faces. Began fading into the fog. It was only a postcard from her ophthalmologist that made me think, oh yeah…Mom’s glasses are not doing the job. Duh…

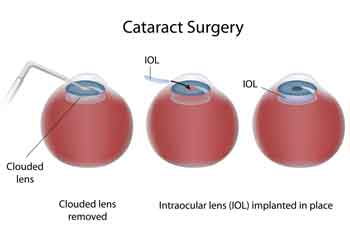

Turned out it was cataracts on top of macular degeneration (which we knew about). The question was, if the cataracts were removed, would she see better? Or was the macular degeneration too advanced? A surgeon said that removing at least one cataract might allow her to see the food on her plate. look at this resources.

The Big Day

On the appointed day, things went smoothly, and I don’t mean just the surgery. Mom was not in one of the all-day slumbers we so often find her in when we visit. The wheelchair did fit in the car. We made it to the bathroom in time and didn’t need the extra set of clothing. The colostomy didn’t leak—what a morning! Oh, and the doctor said the surgery went just great. Mom, unaware that she’d had surgery, broke into song in the recovery room, triggering a quartet with me, my sister, and a very agreeable nurse. That was all before the patient discovered the patch taped over her eye. Oh boy.

Her royal highness was not amused, and the nursing home was an hour’s drive away. All too familiar with Mom’s psychedelic monologues, we knew the usual rejoinders (“uh-huh, I see, oh…right”) were not going to cut it. My sister and I had usurped her authority, and there would be hell to pay. Especially for the nursing staff.

She spent that night warring with her keepers over the patch. (It was written all over their bloody faces when we picked her up the next day for her post-op checkup.) Still, they were buoyed when she returned a new (patchless) person: smiling warmly and saying, “Hi, how are you today?” Looking around the place: “Isn’t this just beautiful!” Describing the view from a window. She admired my dress, then looked, really looked into my eyes. She hugged the family photos to her chest and laughed, sang, chattered (get this) in logical English. Okay, not logical all the time…but so improved in cognition that we were truly stunned.

“Mom’s back,” I said to my sister, through tears.

Don’t Give Up

The takeaway on this: don’t ever give up on quality of life. Override the dementia. Take a chance if offered one. Our mom, our songbird-queen, the indomitable Ruthie, retooled in a single day, taking a leap back from the ridiculous to the sublime. And there’s still a little time.